- Home

- Jeff Sutton

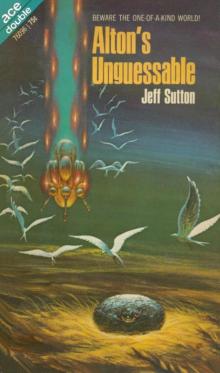

Alton's Unguessable

Alton's Unguessable Read online

Table of Contents

Alton'S unguessable by Jeff Sutton

ONE

TWO

THREE

FOUR

FIVE

SIX

SEVEN

EIGHT

NINE

TEN

ELEVEN

TWELVE

THIRTEEN

FOURTEEN

Alton's Unguessable by Jeff Sutton

ONE

The birds watched the strange ship from space come down.

Scores of bright beady eyes gazed upward into the sapphire blue sky as the huge, cylindrical vessel drew closer and closer. The birds had known the ship was coming; they had sensed its vibrations in the atmosphere long before it became visible. Immediately they had settled in the tall grass, their eyes turned expectantly in the direction from whence the vibrations came.

They had not long to wait.

As the big ship descended slowly, passing off to one side, the birds rose and followed it. After a while, the ship ceased its forward motion, hovering at low altitude before finally settling toward the flat, grassy plain.

By then, the birds were very close.

It had been a tense moment when the big spaceship first came into view—the most intense the birds could remember in more than fifty thousand revolutions of the planet around its blazing- blue-white primary. Before then, time was a memory of incredible space, of the edge of the universe where nuclear fires had banked, of nine small shapes hurtling through the awesome chasms of the sky, and of a race now dead for more than a hundred billion years.

Not that these same birds remembered back through that lonely, empty time. It was the thing in the minds of the birds that remembered. In reality, the thing that lived in the minds of the birds was a unity—a oneness—that could fragment its mind into innumerable parts in which each fragment could enter and subjugate a host, acquire its thoughts and memories, see and hear and feel through its sense organs, and direct its actions while its own weak and immobile body lay securely hidden. More, through its hosts, it could exert the mind power. But all the while, it remained a unity. Each and every mind fragment was tied telepathically to each and every other mind fragment and to Uli, the thing itself.

Uli! Only blind chance had brought him to this remote planet more than fifty thousand years before. With a hard-shelled body protecting him from the harshness of space, and his life sustained by the weak radiations between galaxies, he'd landed here during one of his many millennia-long periods of sleep. Had he been awake, certainly he would have bypassed this planet for one closer to the dense region of burning stars. Sleeping, he'd had no choice; his mind had been programmed to seek a world having the physical characteristics favorable to his kind. As it was, he'd awakened in the hills close to this same grassy plain, which in those long-ago years had formed the basin of a shallow inland sea. Not that Uli was a "he" nor even a "she," for reproduction by fission is sexless, but the strange bipeds he'd found on the planet had worshipped him as a god and had thought of him as a "he"—a male thing—so he had come to think of himself as male.

Despite the sprawling cities and strange mechanical contrivances which marked the promise of intelligence, Uli quickly perceived that the bipeds (such ungainly forms!) would never reach the stars; their blue-white sun was too remote from its neighbors. Neither did they exhibit the potential for the intelligence necessary to solve the problems inherent in such travel. Because they never could serve him, he quickly decimated them (even while enjoying their worship, which he had found quite ego-satisfying). It had not been an act of cruelty, but of necessity, for the law of the Qua stated quite clearly that no major life form could be allowed to survive except those directly beneficial to the Qua. At times he'd wondered why, but his memory banks returned no answer.

Later, annoyed by the sight of their silent cities, he had erased almost every vestige of their civilization from the face of the planet. Occasionally, through the eyes of a host, he would discover yet another remnant and would quickly obliterate it. Not even its rubble would remain.

By the same reasoning, he had annihilated every major life form on the planet save that of one species of bird. The sharpest of eye, the keenest of ear, the greatest in mobility, this species also possessed a fecundity that guaranteed he would never be without hosts. In that regard they could serve him—until a proper host came.

Came? The word grew to haunt him.

As a small part of his consciousness measured time by the planet's rotations and its revolutions around the sun, and alerted him to the thousands of years that were passing, he'd become more and more uneasy. To reach the great central star-swarms that most certainly would abound with suitable worlds, he required a host with an interstellar technology. When would such a host arrive? Through the eyes of the birds—ten thousand birds that girdled the globe—he watched the skies. And waited.

Millennia passed.

He had to reach the heart of the galaxy! The knowledge, screaming up from his memory banks, became a frantic pressure. Only then could he safely fission, to commence anew the chain of life through which his kind eventually would rule the countless star islands that comprised the Middle Universe. That purpose, had been instilled in his consciousness before the First Awakening—before he and eight companions had been propelled inward from the dying edge of the universe by the combined mind power of the Qua.

The Qua! Whenever Uli thought of his race, which was often, it was with fierce pride. Had not the Qua risen in the Dawn of the Prime Creation to rule more than a million sun systems through the mind power alone? The First Life, the greatest… It was all there in his memory cells. The immortal Qua!

But the nuclear fires had been banked; the edge of the universe had died. And the Qua, their bodies immobilized in the millions of generations they had ruled through lowly life forms, had died with it. Their last attempts to separate their minds from their bodies—to exist as pure, immortal thought in absolute space—had failed. And by then, night was falling over the stars.

Uli had been one of nine chosen for the first desperate effort to project a new Qua culture into the incredibly remote central realms of the still fiercely-burning star islands. Propelled inward with his companions by the combined mind power of their race, he alone had reached this remote planet. Now the glory of his race lived only in his mind, and he would fulfill their destiny. Here, in this billion-star galaxy, the Qua would rise anew. That was the prime purpose of his being.

Still, he had begun to discern the day when the planet would die, as all planets must. Certainly it would be cindered in that distant time when the great blue-white sun passed into its nova stage. When that time came, he would die. He would die! And Death was a haunting specter. His own death meant the death of the Qua… The prospect was frightening. Then, miraculously, vibrations had come from the top of the atmosphere.

Watching through scores of eyes as the huge ship settled toward the grasslands, he exulted that his liberation was near. The geometry of the ship bespoke the intelligence of its builders. To reach this planet at the very edge of the galaxy where stars were sparse, its builders must have solved the complex problems of space discontinuities and the multiple nature of time, for he was certain that such beings were too short-lived to move between the stars otherwise. Only the Qua were immortal! But this was a ship with a race that could carry him afar.

Idly he wondered how long it would take to conquer the galaxy.

Roger Keim, the T-man, gazed uneasily at the banks of telescreens. Tall and dusky of skin, with the yellowish eyes characteristic of the second planet Klasner from the golden sun Korak, his lean face showed none of his perturbation. But it was there; and he wondered why.

Vast grass

y plains, forested mountains, a plenitude of fresh inland water, three immense oceans with two large moons in the sapphire sky to raise their tides—a waiting world with no major life of its own—it appeared ideal for human development. A one-of-a-kind planet that might be found but once in the exploration of a hundred random star systems. And they had found it! The knowledge lay in Captain Woon's weathered face, in Myron Kimbrough's intent eyes in the tautness of the group of scientists who had come to the command bridge to witness planetfall. All were quiet intent.

A world in a thousand!* Still a faint and eerie sense of impending peril persisted. A prickling, vague and indefinite, screamed alarm from somewhere deep in Keim's subconscious. The first inkling had surged upward into his awareness shortly after the survey ship Alpha Tauri had broached the planet's atmosphere. Something about the planet was wrong!

Several times, starting to speak, he had refrained; the uneasiness was simply too nebulous for him to define. Too, every safety precaution had been taken; Captain Woon had made certain of that. Following the standard procedures for landing on a strange planet, the Alpha Tauri had circled the world time and again while scores of sensors recorded every aspect of its surface, seas, and atmosphere. Scores of minisats, launched into varying low-level orbits, had failed to detect the presence of a single energy source save those provided by nature itself. In effect they said: no danger, no danger. The information from the sensor complex, fed into a computer and converted into a micro-simulacrum of the world now unfolding below, had revealed absolutely nothing of a perturbing nature. Even the banks of biosensors, probing for the existence of major life forms, had found only birds.

A world created for the evolution of higher life in all its varied forms, yet all but devoid of such life. Was that the cause „ of his alarm? Had evolution somehow passed this world by? The questions baffled him.

With the Alpha Tauri moving slowly above the grassy plain, he became conscious of the sensation of pressure within his brain—a pressure that resolved itself into a low, muted thunder like the crash of waves on a lonely beach; it waxed and waned in that selfsame way.

He cast a quick glance at the others: Harlan Duvall the psychmedic, Sam Gossett of Chemistry, Alton Yozell of Biology, Robin Martel, the pert blonde meteorologist. All were absorbed in the scenes unfolding on the telescreens. The thin, gentle face of Arden, the astrophilosopher, did have a speculative expression; but no one else appeared unduly worried. To the contrary, Astrogator Ross Janik looked slightly bored. So did Paul Rayfield, the physicist. Myron Kimbrough, the gaunt, stoop-shouldered chief scientist who stood alongside Captain Woon, had the impatient look of a man whose guests were late for dinner. Dark-haired Lara Kamm of Alien Cultures, wrapped in her own introspection, stood slightly apart from the others with a pensive expression on her oval face. Only the dusky eyes of Karl Borcher, the ecologist, were frankly puzzled.

"A real winner," someone murmured. The group stirred at the break in silence. Keim placed the voice as that of Ivor Bascomb, the botanist. Although no one answered, Keim knew that Bascomb had reflected their hopes; this world did look like a winner. Although the small part of the galaxy that had been explored teemed with planets, only an exceptional few had proved suitable for human development. On the present expedition—officially designated as Survey 92—this was the first of dozens of worlds that held a potential for mankind. But why his worry?

As his eyes inadvertently caught those of Lara Kamm, she quickly shifted her gaze. He was used to that. Although he'd found her pleasant enough during their occasional encounters in discussion groups or in the staff wardroom, she had taken more pains than most to avoid him. Few men or women, especially women, felt at ease in the presence of a telepath. He'd learned that lesson well while still a small child. On his world, Klasner, his few close friends were restricted to those like himself. But that was par for a T-man.

Captain Woon spoke briefly into the communicator. Keim sensed an immediate deceleration; with it he became conscious that the thunder in his mind had increased. Anxiously he scanned the telescreens. To the rear, above the waving grasses, he saw a far-away flock of birds. Studying them, he realized they were flying toward the ship. The telescreens that displayed the view to either side and ahead revealed nothing but grassland. What churned in his mind? What screamed deep down in his subconscious that made him so edgy? He returned his gaze to the rear screen. Sky, birds, grass—under the blue-white sun, the scene held the serenity of a pastoral painting.

The thunder increased, punctuated by static-like cracklings that whipped at his brain; a soundless roaring tide contained within his own skull. Yet it gave the impression of a vast sweep of sonic energy assaulting him from all sides.

Captain Woon spoke again into the communicator. Hesitating, Keim swung toward him. "Don't go down," he warned.

"Hold altitude," Woon barked. He whirled toward the telepath. "Why not?" His heavy face mirrored the antagonism he so often failed to conceal when in the T-man's presence.

"Something isn't right."

"Danger?"

"I sense it, yes."

Kimbrough, the chief scientist, stepped forward and asked sharply, "Of what nature?"

"It's like thunder," he explained.

"Thunder?"

"Silent, crackling thunder; that's my impression."

"Is it a threat?"

"I feel very strongly that it is. Not that I can define it."

"Did you just notice it?"

"The onset came shortly after we commenced planetfall." He explained his earlier uneasiness, how it had increased, and the static-like cracklings that now whipped in his brain.

Kimbrough shook his head slowly. "There's not a single structure, road, or artifact of any kind on the entire planet."

"Are those things concomitant necessities for the presence of intelligence?" asked Keim.

"In our experience, yes."

"Must they be?"

"Logically, yes." Kimbrough glanced at Lara Kamm. "But I'll defer the answer to Alien Cultures."

"We can only draw from history," she reflected. Eyes averted*from the T-man, she continued, "We've never encountered even the most primitive of intelligence without it having something in the nature of artifacts. Especially at a level sufficiently high to be threatening, can true intelligence exist in the complete absence of artifacts? My impulse is to deny it. In essence, we measure intelligence by performance and by what a race creates. How good that criterion is, I hesitate to answer. After all, we've touched but a small corner of the galaxy. Perhaps…" She shrugged.

"Perhaps what?" Kimbrough prodded.

She smiled slightly. "I only meant to convey how little we really know."

"The biosensors didn't indicate a single life form higher than birds," he observed. "And still don't."

"What is a major life form?" interrupted Alton Yozell. As attention turned to the biologist, he continued. "Is the criterion size, structure, intelligence, the tool-making ability, a combination of all that, or is it something else?"

Kimbrough asked, "What do you have in mind?"

"Only that when we speak of a major life form, we define it in our own terms, by what we know. Because we do, we rule out other possibilities."

"What other possibilities?"

Yozell shrugged. "Everything that lies within the realm of the unguessable, if I can put it that way. Or perhaps I should say whatever lies beyond our senses. We define that which is perceptible, nothing more. While that's quite understandable, should we accept our sensory limitations as the ultimate of possibilities? When we transcend such senses with instruments, we accept their findings. But why should we stop there? I don't know, but I'm not at all certain that what knowledge we have constitutes the ultimate authority. Perhaps far more than we suspect lies beyond the threshold of our awareness."

Kimbrough smiled patiently. "I wouldn't worry about the unguessable, Alton."

"Perhaps we should." It took Keim a moment to place the speaker as Karl Borcher, t

he ecologist.

"Would you amplify that?" asked Kimbrough.

"Like Roger, I've sensed something quite wrong, although I hadn't thought of it in terms of threat," explained Borcher. "But the planet's ecology bothers me; it doesn't make sense. The environment screams for animal life, an abundance and a diversity of it, but it's not there. Only birds and small rodents. And if the readings on the biosensors are right, that life is restricted to but one species of birds."

"I hadn't noticed that." Kimbrough was startled.

"Their life grams are the same."

Kimbrough walked over to the readouts and scanned them. "I'll grant you that," he admitted.

"There's a lack of harmony, a lack of balance, at least as we know it," persisted Borcher. "If major life forms haven't developed, why not? If they have, what became of them? How could a single species of bird develop to its present high order, but not others? Evolution, for all its random nature, is quite an orderly process. We've cited our experience, but have we experienced this situation before? Never. We'd better take a second look before we go down."

"The instruments have shown us all they're ever going to show us," Kimbrough remarked wryly.

"Shouldn't we expect new situations?" interrupted Arden, the astrophilosopher. Keim switched his gaze. The fragile bone structure of Arden's face, with the high brow and sensitive mouth, gave him a perpetually inquiring look. He continued, "Should we expect all of the galaxy to obey the same laws, follow the same lines o£ evolution? I don't believe so."

"It's the absence of evolution that bothers me," Borcher returned.

"Or is it just that we don't perceive it?"

"You're saying?" asked Kimbrough brusquely.

"Not saying, merely suggesting," Arden corrected.

"Suggesting what?"

"I'm inclined toward Alton's suggestion. Perhaps our sensory apparatus is too limited for this world."

"You're postulating the existence of life down there?"

"Speculating."

"Even speculation should have a basis in fact."

Alien From the Stars

Alien From the Stars The Boy Who Had the Power

The Boy Who Had the Power First on the Moon

First on the Moon The Man Who Saw Tomorrow

The Man Who Saw Tomorrow Alton's Unguessable

Alton's Unguessable