- Home

- Jeff Sutton

Alton's Unguessable Page 2

Alton's Unguessable Read online

Page 2

"I don't hold to that view, but in this case it does." Ar-den swung his gaze to the telepath. "Roger is gifted beyond most men. His alarm is my alarm."

"Would you have us write off this world?" demanded Kimbrough.

"I haven't recommended that."

"Karl?" He switched his attention to the ecologist.^

Borcher rubbed his jaw. "No," he said finally, but his face held a defeated look.

"I believe you're unduly worried," Captain Woon interrupted. "What possible threat could prevail in a world completely /devoid of artifacts? If an alien form of life exists that we can't sense, we can at least sense material things, and they're just not down there. Not artifacts."

"We still have Alton's unguessable," Kimbrough remarked dryly.

Woon shook his massive graying head. His face, scorched by the radiations of scores of suns, mirrored incredulity. Gesturing toward the telescreens, "We can throw a force field around the Alpha Tauri that no weapon known to man can penetrate," he said. "If necessary, we can scorch the life from the face of that planet, right down to the last single-cell organism. Alien or not, the danger is negligible. My recommendation is that we land." His eyes challenged the T-man.

Keim smiled soberly. "The decision's not mine," he answered.

"Anyone disagree?" asked Kimbrough. When no one answered, he directed his attention to the telepath. "Still sense the thunder?"

"As strongly as ever," he admitted.

"But nothing specific?"

"Nothing." He shook his head reluctantly.

Kimbrough asked carefully, "But the threat is definite?"

"I have that feeling, yes."

Kimbrough sighed and looked at the captain. "I believe we should land. With weapons ready," he added. Borcher started to demur, but refrained. Keim saw his troubled glance return to the biosensor readouts.

Woon barked several commands into the communicator and the Alpha Tauri began settling toward the grassy plain. Keim noticed how quickly, how intently, all eyes returned to the telescreens. He noted, too, that Kimbrough's formerly impatient look had given way to a frown of concern. Keim felt the desire to read his mind, but didn't. It was an ethic he'd always observed and had to observe if he were to remain among his kind. It was only through their trust that he could be tolerated. That had been drummed into him since early childhood when his rare talent first had been discovered. He'd chosen to live among scientists in the belief they were more understanding; and on the whole he'd found them to be so. Still, many of them (perhaps unknowingly) had exhibited their wariness of him. Like Lara Kamm. A T-man… The ship's pariah, he reflected ruefully.

But he could appreciate Kimbrough's feelings. And Captain Woon's. A planet with such seeming potential scarcely could be abandoned in the face of an intangible threat. But did they realize that the mind of a total telepath often constituted a sensor that man otherwise could never duplicate. Time and again, surprised at his own abilities, Keim knew that his special sense by far exceeded that of any telepath of his acquaintance. Because he suspected that Kimbrough had long since assessed that capability, he was certain the chief scientist would be extremely cautious. He also had to admit that Captain Woon, if anything, had understated the Alpha Tauri's destructive capabilities. The ship not only could scorch all life from the land, sea and air, but could also reduce the entire planetary surface to rubble.

He returned his attention to the crackling static in his mind. His eyes closed to the telescreens, he tried to decipher its meaning. While the jumble seemed absolutely unintelligible, not so the sense of threat. Danger! Danger! Danger!

The alarm screamed from deep in his mind.

TWO

Keim blinked in the glare of the blue-white sun. Following the long adaptation to the ship's lighting, the natural radiation momentarily pained his eyes. This sun, blazing in a violet sky, was brighter than most. Its rays felt pleasantly hot against his skin.

Myron Kimbrough, the chief scientist, had named the blue-white sun "Krado" in honor of a distinguished former director of the Survey Service. Thus the planet merely was designated as Krado 1, and the two large moons that lazed placidly in its sky as K-l.l and K-1.2. Keim realized that any name given at this time had no official sanction. Later, when the new system was drawn to the attention of the Imperator and Council of Overlords, the official designations would come. He held scant doubt but that they would reflect the names of the Empire's politically great. Still, to the scientists, the sun would remain as Krado. They had that doggedly insistent way of honoring their own.

A dozen independent teams were preparing to bleed Krado V of its secrets. Working smoothly and efficiently, each member of the science staff would conduct his own specialty. For Keim, the scene held a long familiarity; it was one he'd witnessed on more than a score of planets.

Off to one side, blonde meteorologist Robin Martel was launching a high-altitude radiosonde. Although quite primitive, the method returned a quick analysis of short-term weather. Later, the more sophisticated minisats would return complete meteorological data. From this, the computers would extrapolate seasonal forecasts including temperature, humidity and prevailing winds, that could be expected to jibe within a narrow margin of reality.

Ivor Bascomb and Alton Yozell, the botanist and biologist, took off in a twin-seat skimmer for a quick look-see of the surrounding area. Keim watched the vehicle climb into the blue before leveling off. The geologist, Burl Ash-ford, was "tentatively examining the soil. Short and slender Henry Fong, the brown-faced historian whose ancestral home had been in the Asian world of Old Earth, was photographing the activities as he spoke into a recorder. Scores of birds wheeled overhead. A pleasant scene.

Keim's thoughts turned inward. The muted thunder punctuated by the crackling noises still filled his brain. So did the sense of threat. If anything, the inner tumult was greater than ever. He had the feeling that if he could concentrate deeply enough, search the inner corridors of his mind, he could discern the meaning of his disturbance or at least glimpse some clue to its source. As it was, it was just a something that lurked beyond the borders of his consciousness.

He speculated, as he had before, on why he could usually penetrate the subconscious of other minds, yet never his own. When he tried, he had the sense of encountering what seemed a physical barrier. It was that way now: a partitioning of his mind into the conscious and subconscious, with no avenue between. Nothing but. the feeling that his subconscious knew what the crackling thunder was all about—knew but couldn't project that knowledge into his awareness. He was a man cut off from himself.

Could this world actually be as peaceful as it seemed? Or, as Arden had suggested, were they looking without seeing? He wondered what his impression of this world might be were it not for the conflict in his brain. Looking over the sea of grass, he tried to assess it.

A quiet planet. Hospitable. It could be Klasner, Jondell, Tarth, or Old Earth. A waiting world. An all but lifeless world. Why? Life springs from a common cell and diversifies into all its thousand million forms. It was so throughout the known galaxy—but not here. Why? We reason, we analyze, we deduce, yet we always circumscribe our thinking by the basic laws we call truths; we start from what we know, and usually end there. Alton Yozell's words. But why must we judge this world by the worlds we have known, and judge life by the life we have known? More pertinent, how could we understand that which is beyond our power to perceive? A basic question: can intelligence exist without artifacts? Lara thought not, but was doubtful. Why? Because of his own reaction? But Alton had been doubtful too. And Borcher. And Arden. Equally important, how could he interpret his uneasiness in terms he could understand? Or had man finally come face to face with the unguessable? We should get out, get out while we can!

Get out? Keim had to scoff at his foreboding, more so because he had never been one to scare. Yet, with more than a score of alien planets behind him, he had never felt the intense disturbance that gripped him now. He took stock of the grasslands, of

the birds wheeling above, of the sapphire sky and the single moon now drifting through it, of the cloud banks with their pastel tints that edged the horizon. Peaceful, yes. Nothing to negate it but the crackling thunder in his mind and the prickling that lay deep in his subconscious.

Lara Kamm emerged from the ship, pausing to glance around. Despite the emerald-green field suit designed strictly for utilitarian use, Keim thought her a striking figure.

Yet, even at the distance, he could discern that strange, pensive expression that was so much a part of her. Or was it just that she was more introspective than most? Whatever the reason, her only close friend seemed to be Sam Gossett, the aging chemist.

His musing was broken as Captain Woon came toward him. In Keim's view, Woon symbolized the prototype of the deep spacer: blunt, straightforward, quick of decision, a man to whom a planet was just a way station, a place to pause while skipping between stars. Likewise, in the manner of spacers, he held a slight contempt for the planet-bound trillions who had never known the glory of the stars. He held a thinly-veiled contempt, too, for things he failed to understand, such as T-men. Contempt and antagonism. But he was'"lord and master" of the ship, just as Myron Kimbrough was "lord and master" of all exploration and research. While Keim had never felt more than passably cordial toward either of them, he had to admit that they made an excellent team.

Woon paused a few steps away. "Still feel the same?" His tone suggested an attempt to disguise his deeper feelings.

Keim nodded. "But I still can't say why."

"Everything appears in order." Woon glanced musingly around. "Kimbrough believes it's a natural for colonization."

"We can hope so."

"Nothing's certain," Woon conceded. "I've seen strange things occur."

"Let's hope not here," he answered dryly.

"I don't expect to, but we're ready." Woon squinted at the sky, his weathered face taking on a nostalgic look. "We're at the very rim of the galaxy, Roger, the farthest man has ever been in this direction. Beyond this sun lies nothing."

"It's a big jump," he acceded.

"Too big." Woon's voice held a faint regret. "It'll take another million years to fully explore this galaxy, but I feel the barrier all the same. I suppose that's the mark of a spacer."

"And the scientist," Keim ventured. "The unknowable always haunts us."

Woon mopped his brow. "There are scores of plains that would afford equally good bases. Do you believe we should try another?"

He shook his head. "I don't believe it would make much difference."

"What you sense isn't local, is that it?'*

"That's my hunch." , "That's not much to go on, Roger."

Keim smiled wryly. "I'll be the first to admit it."

"I hope you're wrong. I'd hate to have to scorch this world."

"Or any world," added Keim. "That's a rough solution."

"Battles are won by weapons, or perhaps that's just the spacer's attitude."

"That's your province," he conceded.

"Keep plugged in, let me know if you pick up any ideas." Woon waved airily and turned toward the ship.

The day passed swiftly.

Something wasn't right!

Keim awoke, presentiment flooding his mind. The muted thunder and crackling, the warning screaming in his sub-consciounsess, none of that had changed. Yet with it he had the feeling of some ominous presence. Something alien? If it was his imagination, he didn't believe so.

He dressed, breakfasted early and went outside. The blue-white sun, still balanced on the horizon, flooded that part of the sky with the pale shades of dawn. A fleecy cloud, pink-tinged, floated above him in splendid isolation. The grasslands, the purplish hills in the distance, and the sky all seemed gorged with an oppressiveness that filled his being. This world was the home of what?

He gazed moodily around. Almost alone among the scientists, he had no official duties, nor did anyone often solicit his aid. Watching the few early risers proceed with their tasks, he contented himself with the knowledge that there had been times when his contributions had been of extreme value. As on the planet Kale of the dwarf sun Gribbous.

There he'd sensed intelligent thought almost immediately, and traced its origin to the remote village of a pygmy race of stone-age bipeds. Even the Alpha Tauri's all but infallible sensors had failed to detect their presence in the exceptionally heavy jungle growth. More, he'd been able to repeat the mental sound impressions onto a tape and run it through a decoder, producing a vocabulary sufficient to enable Hester Kane, the linguist, to establish verbal contact. Acquiring the language with an amazing facility, Lara Kamm had learned their social organization, legends, theosophy, the scant word-of-mouth history they'd possessed. In turn, she and Hester had presented the natives with the gift of writing which, in almost certainty, would advance the race by thousands of years in a few generations.

He mulled the value of it. The inhabitants of Kale, segregated into a few, small and widely scattered tribes, apparently had lived happily under the dwarf sun Gribbous; but would they be happy henceforth? Now that they had discovered the power of the written word, had seen what tools could accomplish, their lives never again would be the same. Their contentment was gone, past. Now they shouted into the wilderness of the future. Good or bad? He wasn't > certain. Insofar as the Empire was concerned, the value of the expedition would be restricted to a few central memory banks, libraries for scholars and astrohistorians. Officially, as happened in such cases, the planet was decreed off bounds for colonization or exploitation, with only trade necessary to the civilization's growth allowed. In time, perhaps after millennia, the planet might prove an important economic resource. That was what made the Empire great—its ability to plan for ages yet unborn.

Myron Kimbrough dropped his skimmer a few feet away and said, "I'm going to make a quick sweep around. Like to come along?"

He nodded, pleasantly surprised. While cordial enough, the chief scientist had seldom sought his company. As the skimmer rose above the spearlike grasses, Kimbrough asked, "Still feel the same?"

Keim laughed. "Captain Woon asked the very same question."

"We're concerned, Roger."

"Nothing has changed."

"Still waxes and wanes, eh?"

"And crackles," Keim amended.

^Could it arise from a natural source?"

"Possibly, but I doubt it."

"How can you doubt it when you have no idea what it is?"

"It's not so much the mental tumult as it is the sense of impending danger," explained Keim. "Bells are ringing, gongs are sounding…"

"Bells and gongs?" exclaimed Kimbrough. He cast a swift glance at the telepath.

"Figures of speech," smiled Keim, "but I sense a danger all the same. It's like the prickling of the hair at the nape of the neck, an awareness that stabs at you before full consciousness. Intuition? Or is something deep down really pushing that panic button? I can't say, but I'm certain that there is far more to this planet than we know."

"Could it be the newness of this world?"

He shook his head. "I've touched down on a score of new worlds. It's not that."

"Yet we've scanned the entire planet continuously since entering the atmosphere. There are rodents in the grasses, the birds. Nothing more."

"That's the puzzler."

"Damn strange," Kimbrough agreed. "Borcher insists that nature couldn't produce such a lopsided ecology, and I have to say he's right. What does that leave? This planet purposefully has been denuded of life."

"And selectively."

"The birds? That's a puzzle." Kimbrough commenced a slow turn toward a range of low-lying hills that lay like a smoky blur on the horizon before continuing, "But it might have happened long ago, many thousands of years ago. Jungles can swallow cities, erase the worst of scars. Perhaps we're not the first visitors from space."

"Why denude a planet and leave it?"

"A fair question, and the honest answer is that I haven't the

slightest idea. Neither has Borcher. The only thing wrong with the 'dim past' theory is how you feel, what you sense." Kimbrough cast a sidelong glance at him. "If I pinned you down, demanded that you identify the threat, what words would you use?"

Keim closed his eyes, searching his mind. Almost immediately the tumult came to the fore, carrying with it the heavy, pervasive sense of threat. Were the crackling thunder and threat related? He concentrated on the rumbling that seemed to surge upward from the deep grottos of his brain; again it reminded him of the crash of waves on a distant beach. Waves crashing, rolling in, the sibilant hiss of water sucking at the sands as it rolled back down the tidal slopes… But the odd geometry of crackling, although a variable scatter, wasn't altogether random. Pattern? If so, it was as intricately constructed as the music of the classics. Noise, but not discord; not when he sensed certain associations. The tides held pattern, but not intricacy of pattern; that was the difference.

All at once he recalled how he'd first sensed the thoughts of the pygmies on Kale. The memory jolted him. It was like this, but with the stimulus amplified a thousand times, the complexity a thousand times greater. It was as if he'd tapped into a vast alien network. Communication? He felt a sudden chill. It was impossible! Yet, deep down, he knew that it wasn't. To the contrary, once he'd made the connection, the answer seemed self-evident. Aliens! Where, and what kind? Alton's unguessable! He caught Kimbrough's expectancy.

"It's a form of communication," he said.

"Communication!" The word held shock.

"I suspect I've known all along, but the realization just surfaced."

"Aliens." A shiver ran through Kimbrough's gaunt frame. He asked, "Can you tape what you sense, run it through a decoder?"

Keim shook his head. "The language of Kale was primitive, restricted. This is a roar, a thunder, a crackling tumult that can't be broken into phonetics. Not our kind. I couldn't begin to repeat any part of it."

"What makes you so certain it's communication?"

"The pattern." And gazing at the sky, he wondered what lay ahead.

Alien From the Stars

Alien From the Stars The Boy Who Had the Power

The Boy Who Had the Power First on the Moon

First on the Moon The Man Who Saw Tomorrow

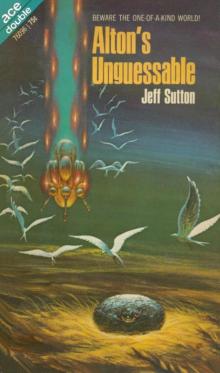

The Man Who Saw Tomorrow Alton's Unguessable

Alton's Unguessable