- Home

- Jeff Sutton

Alien From the Stars Page 3

Alien From the Stars Read online

Page 3

Yes, and on others. Barlo glanced back at the rising sun. It's getting quite warm.

Afraid that the stranger might decide to leave, Toby quickly suggested that they sit in the shade.

His brain spun with the thousand questions he had

to ask. Barlo patted the dog's head and, moving under the shade of a stunted mountain oak, sat on the dry leaves. Toby sat across from him.

"Can you talk using speech?" he asked.

"With difficulty," answered Barlo. His voice, high and reedy, while not unpleasant to Toby's ears, sounded strange. Later he was to think of it as a musical voice, like the high notes of a flute.

Barlo added, "I'll do better before long."

Toby nodded his understanding. "How did you get here?"

Barlo described the disaster and how he had come to land in the nearby hills.

"Where's your ship now?" asked Toby eagerly.

"In one of the gullies." Barlo gestured toward the east. "It's hidden."

He projected an image of the ship in the boy's mind, observing the latter's quick, startled expression followed almost as quickly by a look of understanding.

"How did you do that?" asked Toby.

"The same way I project ideas."

"Telepathic images..." Toby shook his head wonderingly. Or was it telepathy? Not really, for he couldn't read Barlo's mind but could only receive the words and pictures that Barlo projected into his. Yet when Barlo read his mind and projected the answers, it was the same as if he had read

Barlo's mind. Yet it wasn't the same at all; Barlo could open and shut his mind at will, project Page 10

not only imagery drawn from memory but imagery woven of imagination. In a sense, Barlo was the operator of a television station while he, Toby, was the viewer. But the telepathy did not seem nearly so startling as Barlo's ability to draw the contents from his mind instantly and understand what they meant. Equally magical was his ability to project thoughts.

"It's not a matter of the projecting mind so much as of the receiving mind," observed Barlo. He explained that the ability to receive such telepathic images was a function of intelligence, but it was also something more. Some minds, a few, were ready for nature's next step.

"What's that?" interrupted Toby. Barlo explained that most life-forms quite early found their niche and remained there. Insects and birds were typical. But in other forms the evolutionary process appeared unending. Such emerging cultures, if they didn't destroy themselves in the process, eventually reached the stars. But even that was an individual function rather than one of race. In most societies it was the few who led the many. And the next step he'd mentioned was the opening of the mind, its flowering, its receptivity and response to the universe rather than to only its immediate environment. The ability to receive telepathic projections, especially in the form of imagery, indicated the opening mind. As he spoke, Barlo's large violet eyes regarded the boy gravely.

Forgetful of the time, they talked. Toby thought it strange how quickly people could adapt to new situations. Sitting under the stunted oak with Barlo seemed quite natural. He marveled at how quickly his strange companion was adjusting to this world. He was speaking as if he'd known Toby for a long, long time. Toby wished he could meet Grandpa Jed.

Barlo revealed that the name of his planet was Raamz and that his sun was Zaree. As he spoke, he projected a vivid image of incredibly tall pink buildings jutting into a sky in which rode a dusky red sun. The air was alive with vehicles of almost every size and description. "My world and my sun,"

said Barlo. His voice held a touch of pride.

"It's beautiful," replied Toby. No, beautiful wasn't the word; it was fantastic. Fantastic and unbelievable. And yet it wasn't, for a man -- Toby mentally had translated "creature" into "man"

-- from the stars sat opposite him now, telling of the wonders of the universe. But no one would believe him, Toby decided. Except Grandpa Jed. Gramp would believe him. So would Linda Jansen, who went to school with him. Linda was awfully smart. Perhaps there were a lot of people who would believe him, but he wasn't too certain of that.

He listened avidly as Barlo told him more about himself.

He was a planetary archeologist. But instead of concentrating on a single race he roved the known galaxy, searching out the artifacts, inscriptions, and sepulchers of the distant past, whatever their forms. He projected an image of the ruins of an ancient city on a bleak and shadowy plain. The sun above it was purplish red. "The past yields the key to the future," he explained.

Toby told him about his own dream of becoming a geologist. He opened his specimen bag and displayed several minerals he had found that morning. Barlo examined them interestedly as Toby described their physical and chemical characteristics. He explained that his interest was not solely with rocks but with all of nature; he wanted to know why things were as they were. Barlo could understand that; Toby could see it in the large violet eyes.

Barlo said, "I believe you will make a very fine geologist." He glanced toward the climbing sun.

Suddenly Toby realized that his companion was beginning to suffer in the growing heat and that he kept his eyes averted from the harsher light.

"Come home with me," he urged.

Barlo shook his head, a gesture he'd learned from the boy. Toby suppressed his disappointment; he'd been looking forward to having Barlo meet his grandfather. "You can't stay here," he protested. Barlo explained that he would be rescued.

Page 11

"When?"

"Eventually."

"How will they know where you are?" Toby argued. Barlo explained that a search would have been launched immediately when the big Zemm liner had failed to reach its destination. Even now rescue units Would be combing every moon and planet along the big ship's flight path. He explained about the capsule he'd launched into orbit and added that he also could transmit a distress signal that would guide any nearby craft to him.

"But they might not come for a long time," protested Toby.

"It shouldn't be too long." The large violet eyes regarded him steadily.

Toby felt a sudden suspicion.

"There's some other reason you won't come," he accused.

The faint smile that came contrasted strangely with Barlo's suddenly solemn demeanor. "I'm afraid," he admitted.

"Of my people?" Toby suppressed a start. "They're not all like the hunters."

Barlo asked quietly, "What do you believe might happen if word got around that a creature from the stars was staying with your family?"

"Yeah." Toby licked his lips drily. He could see that. The people would come flooding in from San Diego by the thousands. Even from Los Angeles, perhaps farther. There'd be reporters and TV cameramen all over the place. The flying-saucer stories came vividly to his mind. A lot of people would be scared. They might even think Barlo was an invader of some sort.

"It's bad enough that I flew over the highway," observed Barlo.

"They probably thought it was some kind of an experimental ship," Toby suggested hopefully.

"There are a couple of Air Force bases on the other side of the mountains."

"It's possible." Barlo didn't appear convinced.

"Are you going to stay in your ship?"

"I can't." His eyes rested on Toby's face. "If the ship is discovered, I'll have to destroy it; and if I were in it, I would die. I don't prefer that."

"Why would you have to destroy it?" Toby didn't think it made sense.

Barlo regarded him thoughtfully. "It has secrets," he said finally.

"The propulsion system?" blurted Toby. "Is it a star drive?" He knew all about star drives from science fiction.

"Not the scout pod." Barlo shook his head. "But the principle is similar. It could lead to the development of such a drive."

"What's wrong with that?"

"The people from Earth might not be ready for the stars." Barlo stilled Toby's protest with a gesture. He explained that races which went to the stars too soon usually end

ed disastrously. How could a race that didn't fully understand itself understand an alien culture? How many wars had Earth had?

There hadn't been an interstellar war for more than a million Earth years.

As Barlo spoke, Toby felt his protest weaken and finally vanish altogether. He could understand Barlo's fears, and he had to admit that they were founded on a firm basis. There was nearly always war someplace on Earth, and usually more than one. But the stars! He felt the keen edge of disappointment to think that the stars would be denied to Earth, even though the people of Earth were not yet ready for them. But some people were! He wanted to say that but realized it would do no good; a few people couldn't go to the stars without opening the door to everyone.

He finally asked, "Where will you stay?"

"In the hills."

"You can't. Besides, there are always hunters." Struck by an idea, he explained that there was a barn behind his house, that nobody but he ever went into the hayloft. It would be easy for him to Page 12

bring Barlo food and water. "No one would ever know you were there," he finished.

To his intense satisfaction Barlo agreed that it might be a suitable place. Toby sprang to his feet, walked to the brow of the hill, and looked around. The hunters were nowhere in sight, nor could he see a sign of anyone.

He automatically plotted a course which would keep Barlo in the shade as much as possible, yet allow them to keep a good lookout. At his gesture, Barlo patted the dog's head and came out from beneath the overhanging branches. Toby noticed that he kept his eyes averted from the sun.

With Barlo close at his heels, Toby followed the dog down the hillside.

Conscious of their exposed position, he moved swiftly toward lower terrain where the trees and shrubs grew more thickly. Once, glancing back, he was struck at how lightly and agilely Barlo moved. Barlo caught his look and explained that Earth's gravity was somewhat less than that on his own planet.

He had been on worlds, he said, where the gravity was so great that it had been tiring to stand for even a few moments. Toby didn't think he'd like that.

Lower down he followed a treelined ravine, careful to keep in the shade as much as possible.

Once they halted as an airliner passed overhead. High in the sky, it looked like a diminutive arrowhead agleam in the sun. Toby speculated on the alien's thoughts as he watched it. It struck him that to a race which traveled among the stars the airliner would resemble a primitive toy.

The reflection was not good for his ego. A low whine came from somewhere to their south.

Barlo paused and cocked his head.

"A truck on the highway," explained Toby. A short while later they sighted a double concrete ribbon curving up the side of a distant hill. The trucks and cars that sped along it looked like minute bugs. Toby explained that the highway, called Interstate 8, provided the main surface route between the coastal city of San Diego and the big cities to the east.

The hills opened into a wide, fertile valley where cattle and horses grazed in fenced green fields.

Scattered here and there were groves of eucalyptus, gnarled sycamores, and elms which drooped in the summer heat.

Crossing the southern end of the valley, the highway twisted up the slopes to the east. Several structures placed amid widely separated groves of trees flanked the highway on either side.

Toby halted abruptly, apprehensive at the sight of several dozen cars parked around a stone and plank building that housed the general store.

Although cars often stopped there, he'd seldom seen more than three or four at a time. Barlo's ship! The rumor was already spreading. He confided his suspicions.

"I suspect you're right," acknowledged Barlo. "I'm certain I flew over this valley."

Toby gazed indecisively at the highway. "It'll be safe in the barn," he finally declared. Sending the dog ahead, he led his companion into a shallow brush- lined wash that passed close behind his home. As they drew closer to the highway he heard the faint babble of voices. He signaled Barlo to halt while he edged up through the brush to peer over the edge. Although several large knots of men were visible in front of the general store, he saw none in the fields. But more and more cars coming down the grade from the west were stopping. He moved his eyes uneasily. The area around the corral and barn behind his house was deserted. He signaled Barlo and moved on.

When he halted again, the barn lay a scant hundred feet away.

"Wait," he instructed tersely. Crossing to the barn, he entered it through a side door. The gloomy interior was heavy with the scent of hay. A

horse stirred in the adjacent corral. From somewhere, faintly, came the bark of a dog. Ruff ran in, prancing playfully until Toby shushed him. He climbed a ladder to the loft, spread some fresh hay across the floor, then stepped back to view it ruefully. He didn't think it looked like a proper place for a visitor from the stars.

Page 13

He peered out the front of the barn toward the house, reassured at the deserted yard. His mother would be somewhere inside sewing or cooking, and Grandpa Jed was probably sitting on the porch enjoying the excitement. Gramp would like Barlo; he had that kind of mind.

Caught by the imperative need to hurry, he returned to the wash and beckoned to Barlo. Toby led him to the barn and up the ladder to the loft.

"It's not too clean, but it's safe," he explained. "I'll bring some blankets."

"That won't be necessary." Barlo glanced at the strewn hay and the odds and ends of junk piled against the walls. His violet eyes, in the gloom, caught and reflected shafts of sunlight that filtered through the warped siding. "This will be fine," he declared.

"What do you eat?" asked Toby. He was suddenly afraid that the alien's diet might be something not available.

"No need for food," answered Barlo.

"You have to eat," he protested.

Barlo chuckled and drew what appeared to be a small container of pills from a pocket. "This will do," he explained.

"Is that all?" asked Toby incredulously.

"Sufficient, but I could use some water."

"I'll bring some right away."

"No hurry, Toby."

Toby! The alien had used his name for the first time. Shy and pleased, he wondered if it would be all right to call the other Barlo. It would make conversation much easier.

"I'd prefer that you do use my name," proffered Barlo. Realizing that the alien had read his predicament, Toby flushed. The slight chuckle came again. "I'm somewhat used to it after more than ten thousand years."

"Ten thousand years?" Toby was aghast.

"As time is measured on your planet," explained Barlo. "I'm somewhat older on my own."

"Ten thousand years," he repeated. He gazed disbelievingly at his companion.

"It's an artificial life span," said Barlo. "My normal life span would be perhaps one hundred Earth years, certainly not much longer."

"Transplants?"

"Only late in life. I'm not of that age yet."

"Then how?" he asked helplessly.

"It's more a case of controlling aging and disease."

"If you can live for that long, why not forever?"

"Life is governed by how long the brain lives," observed Barlo. "The body, in a manner of speaking, is a mechanical contrivance. Artificial systems can be used to replace the original ones when, eventually, they do wear out.

But the brain is that house of the spark of awareness that tells you that you are you. You can't replace the house without replacing the 'you'; or if you did, you would be a different identity.

Oh, we can regenerate brain tissue to some extent, nurse it along a bit; but when the inner corridors of that house of awareness die, then the owner of the house also dies. Is that bad?

Death is as universal as life -- a one-to-one ratio, I would say. Suns, galaxies, and entire universes die; but new suns, galaxies, and entire universes are continually being born. That is the way of life...and death."

"But if you are ten thousand y

ears old...?" Toby paused, thinking his question might appear indelicate.

"How much longer might I live? By your standards I'm approaching middle age. I have perhaps ten thousand years left."

Page 14

"Twenty thousand years," Toby breathed. He regarded the alien with awe.

"Do all of your people live that long?"

"More or less. Of course there are accidents, although they are quite rare."

"I can't imagine living that long."

"Would you care to?"

Toby considered it. "Yes," he finally acquiesced.

"Why?"

"Think of how much a person could learn."

Barlo nodded gravely. "That is an excellent reason."

"I would like to see other worlds," said Toby. He quickly added, "I would especially like to see your world. I can't imagine a dusky red sun." He tried to picture how it might look.

"You have a very fine sun," replied Barlo, "even though it is a trifle warm."

When Toby withdrew, Barlo sank down into the hay to contemplate his own situation. It was far more dangerous than the boy realized; he sensed that from what little he'd gleaned from the hunter's minds. Still, the Unity's search and rescue missions should already be fanning out along the starliner's flight path. A few days, as time was measured on this planet, should bring one within range of his simple transmitter.

Briefly he wondered if he shouldn't have remained with the pod. But that, too, could have been extremely dangerous. If the pod were discovered, it would certainly be recognized as from a culture beyond this sun's system. It had been all right to tell the boy, of course; Toby was completely trustworthy. But on a newborn technological world such as this, the knowledge could cause quite a stir. Particularly any suspicion of the existence of a star drive. Now, should the pod be discovered, he was free to destroy it.

Still, he didn't regret the necessity that had brought him to this world. The opportunity to view even a small section of this budding, emotional culture would pay invaluable intellectual dividends. Having thoroughly catalogued and indexed the contents of Toby's mind, he suspected that his knowledge of the planet's physical, cultural, and technological environments probably already exceeded that of the great majority of its inhabitants. He judged it as a world of strange contrasts -- primitive, yet quite advanced, surging with love, torn by hate: an egocentric world in which a few pondered

Alien From the Stars

Alien From the Stars The Boy Who Had the Power

The Boy Who Had the Power First on the Moon

First on the Moon The Man Who Saw Tomorrow

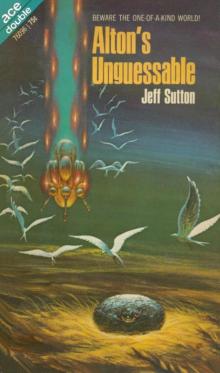

The Man Who Saw Tomorrow Alton's Unguessable

Alton's Unguessable